Learning to draw seems to be one of those items that a ton of people never check off their bucket lists. I’ve met a lot of people who say they’d love to learn to draw, but very few who’ve actually done it. It’s not like they tried and failed, they just didn’t try.

What is it about art that makes this the case? There are a lot of people who’ve never tried to program, because they think it’s too hard, or because they subconsciously think of technology as magic, or something, but these people aren’t wandering around telling me they would love to learn to code. On the other hand, there are a lot of people who say they’d love to go to Europe, but they usually have a definite plan to achieve that goal.

But art is this weird middle-ground; why is that? Maybe, it’s because nobody knows where to start. I’ve written already about how nobody really knows how art works, and I think that’s a lot of the reason for this problem. Still, I haven’t given an explanation of how exactly to get started. So that’s what I’ll be doing today.

The physical components to learning to draw are infinitely easier than the mental ones. In terms of physical actions, all drawing involves is picking up a pencil and a piece of paper and putting one against the other. Mentally, it’s not that easy.

The first mental hurdle you have to get over is to stop worrying about how exactly you’ll bridge the gap between stick figures and portraits. The actual answer is incremental improvement based on iterative comparisons between your art and reality, but you’re never going to get around to doing that if you worry about it.

Think about how you go about getting stronger. You go to the gym. You lift whatever weight you can handle and do as many reps as you can. You go home. You come back to the gym. You lift whatever weight you can handle and do as many reps as you can. You go home. You do this every single day for years. Art works the same way.

That’s really all there is to it. Incremental improvement by putting in a small amount of effort every single day. Here, look at the difference in my art over five years.

The next mental hurdle is getting over the assumption that your art needs to be perfect. When a kid starts drawing, they don’t have that problem; they just don’t think about it. When I started drawing, I wasn’t trying to impress anybody, I just wanted to get better for my own personal benefit. But as adults, we’re a lot more self-conscious than that.

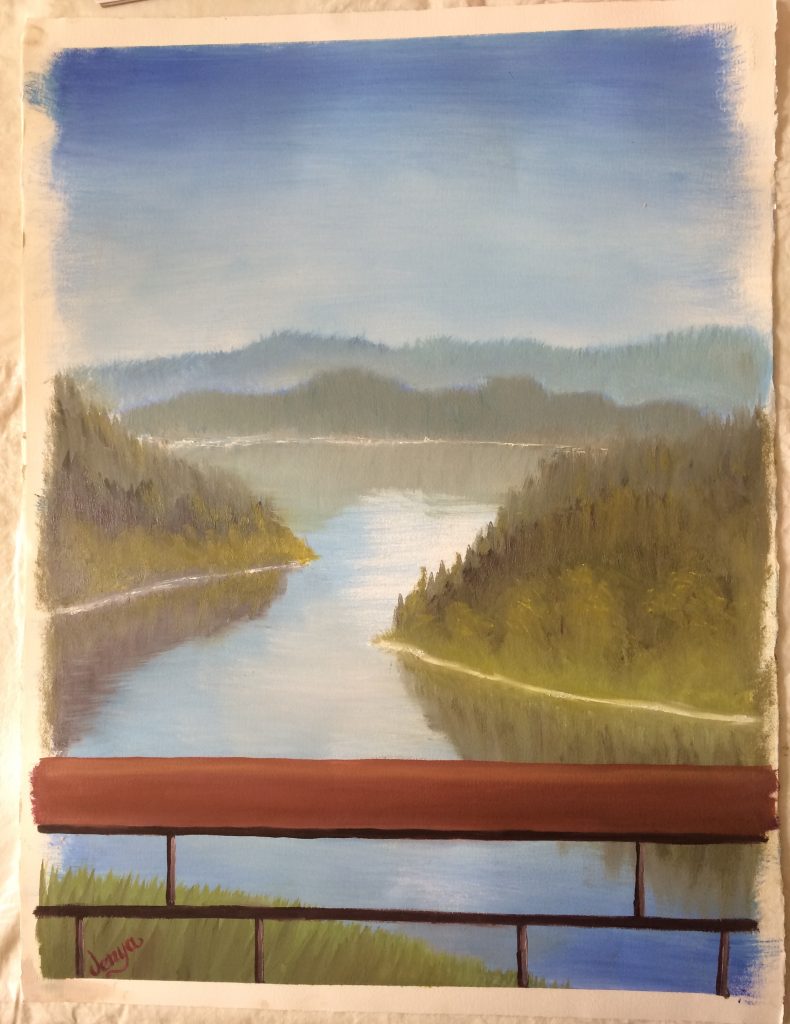

A great trick to help you get over that self-consciousness is to think, “well, that didn’t work.” When (not if, when) you mess up a drawing, or you do something with it that you didn’t like, don’t beat yourself up. Here’s a very recent example. Two weeks ago, I did a watercolor painting of the scene from my back porch. There were supposed to be some hills with trees on them and a house. And oh my god, was it awful. I put way too much paint on my brush, and as a result, the colors were blotchy and the textures and depth vanished entirely. It looked like a shitty backdrop for a childrens’ school play.

But I didn’t beat myself up. Actually, when I came home from class that day (I did this painting for an art class which I’m using as a humanities elective for my degree), I grabbed my terrible painting and I systematically went and found every member of my household so I could show it to them. “Want to see my awful painting?” I asked. Everybody said yes, and everybody laughed at it. I laughed too. It was funny. My brother told me the house I had painted looked like a boat. I laughed harder at that. And the next week, I went back to class, I painted the same scene using oil paints instead of watercolors, and it looked much better.

If you can do these two things—draw every day and don’t worry about messing up—I guarantee you will become a good artist. Still, I’ve got a little bit more info for you today. Here are some Art Tips™ that I’ve learned over the years from fellow artists.

#1: Draw what you see, not what you think you see. This one comes from my dad, one of my art role models growing up. He has this astonishing ability to say things that seem completely useless, but are actually incredibly crucial. This phrase is one of those.

Basically, it means “don’t let your brain, which knows how an object is shaped in three dimensional space, mess with your eyes, which are seeing things in only two dimensions at the moment, since seeing things as they are in two dimensions is crucial to drawing on a two-dimensional piece of paper.” You know that the door is a rectangle, whether it’s open or shut, but don’t let that mess with the fact that when it’s open and facing you, it looks like a trapezoid.

To help you actually implement this advice, try to take your pencil and hold it up in front of reality. Trace the outlines of the thing you want to draw and note the movement of your pencil. It may turn out that the thing you thought was flat is actually not, the thing you thought was long is actually short, etc.

#2: Draw, trace, draw again. I don’t know a single artist who can draw everything with no effort. Every artist has things they’re good at and things they suck at. To help you out with things you suck at, try this.

First, find a photograph of the thing you suck at drawing. Look at the photo, then try to draw the thing. When you’re done with that drawing, put it aside. Next, print out the photo and trace it, in as much detail as you want. When you’re done, put it aside. Finally, do the first step again. Now compare the three drawings. The third one is probably way better than the first.

The act of tracing from reality let you figure out where everything is in relation to everything else and gave you a better understanding of the two-dimensional shape of the thing.

The only thing I’d like to note here is that you shouldn’t use this as a crutch if you’re a beginning artist: there are way more things in the real world around you that you can draw than there are photographs on the internet, and if you really want to practice drawing you should learn to draw from life.

#3: Utilize tutorials. One of the best ways to get advice from artists who you can’t talk to personally is to read and watch tutorials. It helps you to incorporate other artists’ drawing styles into your own. The only problem with art tutorials is that some of them suck, and this can really screw up beginner artists.

Here’s an example of a good tutorial (source: Tumblr). Look at how this tutorial is structured. “Backgrounds generally work like this. Here’s some advice about drawing characters with and without backgrounds. Here are some tips about coloring. Here are some examples from my personal portfolio.” Overall, this artist leaves a ton of the actual art up to you, and simply communicates something they think is important and relevant.

Here’s an example of, if not a strictly bad tutorial, a very mediocre one. Do you see the difference? Instead of providing a loose structure and some advice, this tutorial marches you in lock-step through a pre-defined set of steps. The absolute best thing that can happen with a tutorial like this is the artist comes out of it knowing how to draw one single character in one pose with one expression, with no clue how to generalize that knowledge to anything else. But even that doesn’t happen very often: frequently, a beginning artist gets stuck on one or more of these predefined steps (for example, the eyes or hair, both of which are complicated), and comes out with a mediocre drawing that they don’t like, and with no real knowledge gained.

When you begin drawing, try to avoid lock-step tutorials in favor of loose advice-giving tutorials. You’ll learn more, and you’ll be less frustrated.

#4: Don’t worry about developing an art style. You will develop an art style. It is not optional.

This is because each person views the world (not philosophically, but with your actual eyes) differently: we notice different things, perceive colors differently, etc. And since you view the world differently from everyone else, your art will be different from everyone else’s. Nobody else could create your art because nobody else sees the world exactly like you.

I’ve noticed that a lot of beginner artists look at the styles of artists they admire and they worry about how they’re going to develop their own art style. This partially goes back to “don’t worry about how to get there, just put in the reps every day”, but they also don’t realize that they have an art style by virtue of having eyes and a brain.

If you really want to work hard at developing an art style you like, though, try this. Occasionally, imitate the styles of artists you admire. Because you have no choice but to draw in your style, by imitating their style, you’ll be incorporating both styles together.

Alright, that’s it for today! A lot of these tips are things I wish I had known when I started drawing, so I hope they were helpful to you.